I am the Associate Dean of Carnegie Mellon University's Integrative Design, Arts, and Technology [IDeATe] Program, a role that enables me to do two things I love best—learning from dynamic thinkers and finding creative opportunities in interstitial spaces and places. In IDeATe, I teach a course on spatial storytelling, and I am an affiliated faculty member in the School of Architecture, where I have taught courses on ethics, urbanism, and design research.

An interdisciplinary scholar, my research is situated at the intersection of historical and political geography, infrastructure studies, technology design, and architecture across the late 20th and 21st centuries. My work has been published in venues as varied as The Journal of Historical Geography and the edited volume Algorithmic Life: Calculative Devices in the Age of Big Data. I’m really excited that my first book project, The Global Capture Chain: Infrastructures of U.S.-Managed Military Detainment from Truman to Trump, is under contract with the University of Minnesota Press, a press that has published many of my favorite books.

Before coming to Pittsburgh, I was an Associate Professor of geography in the Department of Social Sciences and History at Fairleigh Dickinson University, where I was named the 2018 Becton College Teacher of the Year and received the 2019 Outstanding Honors Faculty Award for the Florham Campus. In addition to my university classrooms, I've had transformative teaching experiences (through the NJSTEP program) inside three New Jersey prisons, where I ran a few sections of a course on the history of mass surveillance. I was the Chair of the Urban Geography Specialty Group of the American Association of Geographers from 2022-2024.

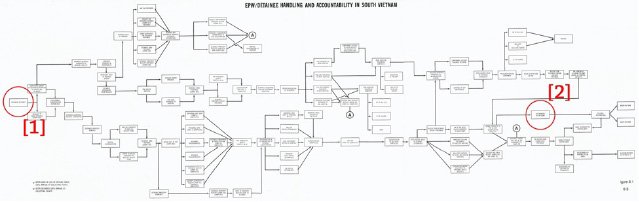

The capture chain: Enemy Prisoner Handling and Accountability in South Vietnam, 1970

Back before all of that, I worked full-time as an architect and freelance graphic designer in New York, Paris, and Iowa. I was an award-winning designer, and in the intervening years I've presented work in the Schools of Architecture at Yale and Syracuse and been on several design juries at Harvard, Syracuse, Pratt, and City College. I still find time to design—fitting in small projects here and there and nourishing my love of furniture design and woodworking.

My CV is here.

Or you can email me.

I'm @rnisa on Bluesky Social.